On June 28, 2024, the Supreme Court handed down its decision in Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo, overruling the regulatory deference in Chevron U.S.A. v. Natural Resources Defense Council. To… Read Moreabout Key Disability Rights Regulations Will Remain Authoritative in the Wake of Loper Bright: A Toolkit for Litigation.

Tag: Title III

ADA Defense Lawyers Prolong Litigation and Postpone Access: A Case Study of Litigation Abuse

[Originally published on the blog of the Civil Rights Education and Enforcement Center on February 27, 2018.] Title III of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) prohibits disability discrimination by… Read Moreabout ADA Defense Lawyers Prolong Litigation and Postpone Access: A Case Study of Litigation Abuse

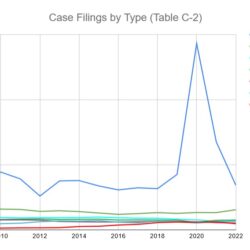

Acheson Hotels v. Laufer: Revenge of the Data Nerds

Fox & Robertson along with a dream team of drafting partners filed an amicus brief today in the case of Acheson Hotels v. Laufer, currently pending in the Supreme Court…. Read Moreabout Acheson Hotels v. Laufer: Revenge of the Data Nerds

F&R, DREDF submit amicus brief in support of proactive ADA enforcement.

Fox & Robertson, along with Michelle Uzeta of the Disability Rights Education and Defense Fund (“DREDF”) drafted an amicus — or “friend of the court” — brief to the Ninth… Read Moreabout F&R, DREDF submit amicus brief in support of proactive ADA enforcement.