In July, we received an excellent ruling from the court on cross-motions for summary judgment in Trivette v. Tennessee Department of Correction. While two of our plaintiffs were dismissed out… Read Moreabout Excellent Order for Deaf Prisoners in our Case Against Tennessee Department of Correction

Tag: Standing

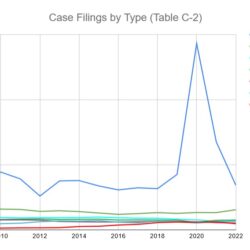

Acheson Hotels v. Laufer: Revenge of the Data Nerds

Fox & Robertson along with a dream team of drafting partners filed an amicus brief today in the case of Acheson Hotels v. Laufer, currently pending in the Supreme Court…. Read Moreabout Acheson Hotels v. Laufer: Revenge of the Data Nerds

F&R, DREDF submit amicus brief in support of proactive ADA enforcement.

Fox & Robertson, along with Michelle Uzeta of the Disability Rights Education and Defense Fund (“DREDF”) drafted an amicus — or “friend of the court” — brief to the Ninth… Read Moreabout F&R, DREDF submit amicus brief in support of proactive ADA enforcement.

This is what a technicality looks like.

Defendant: does a thing that violates a civil rights law. Plaintiff: files suit under said civil rights law. Court: Defendant did the thing but you can’t show that it will… Read Moreabout This is what a technicality looks like.