As explained in the previous post, on May 16, 2025, the Department of Energy (DOE) published a “Direct Final Rule” (DFR) that would rescind the Department’s section 504 new construction… Read Moreabout Update on Trump Administration Attack on Accessible Buildings: Don’t Mess With Our Community!

Category: News

Fight Back Against Trump Administration Attack on Accessible Buildings

On May 16, 2025, the Department of Energy (DOE) published a “Direct Final Rule” (DFR) that would rescind the Department’s section 504 new construction regulation and specifically its incorporation of… Read Moreabout Fight Back Against Trump Administration Attack on Accessible Buildings

Leading Colorado Civil Rights Law Firms Join Amicus Brief Opposing Trump’s Retaliatory and Unconstitutional Executive Orders

Fifteen Colorado civil rights firms were among over 500 law firms — small and large, around the country — who joined an amicus brief rejecting in the strongest terms President… Read Moreabout Leading Colorado Civil Rights Law Firms Join Amicus Brief Opposing Trump’s Retaliatory and Unconstitutional Executive Orders

Settlement Reached in Tennessee Deaf Prisoner Case

Tennessee Department of Correction commits to provide necessary technology and services to ensure equal access. On January 6 — two days before trial was set to begin — we settled… Read Moreabout Settlement Reached in Tennessee Deaf Prisoner Case

Amended Agreement with CDOC Adds Monitoring Team, Reinforces Protections for Deaf and Hard of Hearing Prisoners.

Disability Law Colorado (DLC) reached an amended settlement agreement with the Colorado Department of Corrections (CDOC) following allegations that CDOC was out of compliance with a 2022 settlement. The amended… Read Moreabout Amended Agreement with CDOC Adds Monitoring Team, Reinforces Protections for Deaf and Hard of Hearing Prisoners.

Baltimore agrees to spend at least $44 million to fix inaccessible sidewalks & curbs

In 2021, F&R, alongside our rightous co-counsel at Disabilty Rights Maryland, Disability Rights Advocates, and Goldstein, Borgen, Dardarian & Ho, filed a class action lawsuit against Baltimore City for its… Read Moreabout Baltimore agrees to spend at least $44 million to fix inaccessible sidewalks & curbs

Amicus Victory: Ninth Circuit Holds CA Regional Centers are Places of Public Accommodation.

On Friday, August 30, the Ninth Circuit issued a memorandum opinion reversing what could have been a very harmful district court decision on the definition of “place of public accommodation”… Read Moreabout Amicus Victory: Ninth Circuit Holds CA Regional Centers are Places of Public Accommodation.

Excellent Order for Deaf Prisoners in our Case Against Tennessee Department of Correction

In July, we received an excellent ruling from the court on cross-motions for summary judgment in Trivette v. Tennessee Department of Correction. While two of our plaintiffs were dismissed out… Read Moreabout Excellent Order for Deaf Prisoners in our Case Against Tennessee Department of Correction

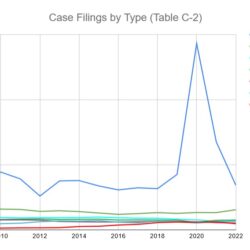

ADA Defense Lawyers Prolong Litigation and Postpone Access: A Case Study of Litigation Abuse

[Originally published on the blog of the Civil Rights Education and Enforcement Center on February 27, 2018.] Title III of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) prohibits disability discrimination by… Read Moreabout ADA Defense Lawyers Prolong Litigation and Postpone Access: A Case Study of Litigation Abuse

Acheson Hotels v. Laufer: Revenge of the Data Nerds

Fox & Robertson along with a dream team of drafting partners filed an amicus brief today in the case of Acheson Hotels v. Laufer, currently pending in the Supreme Court…. Read Moreabout Acheson Hotels v. Laufer: Revenge of the Data Nerds